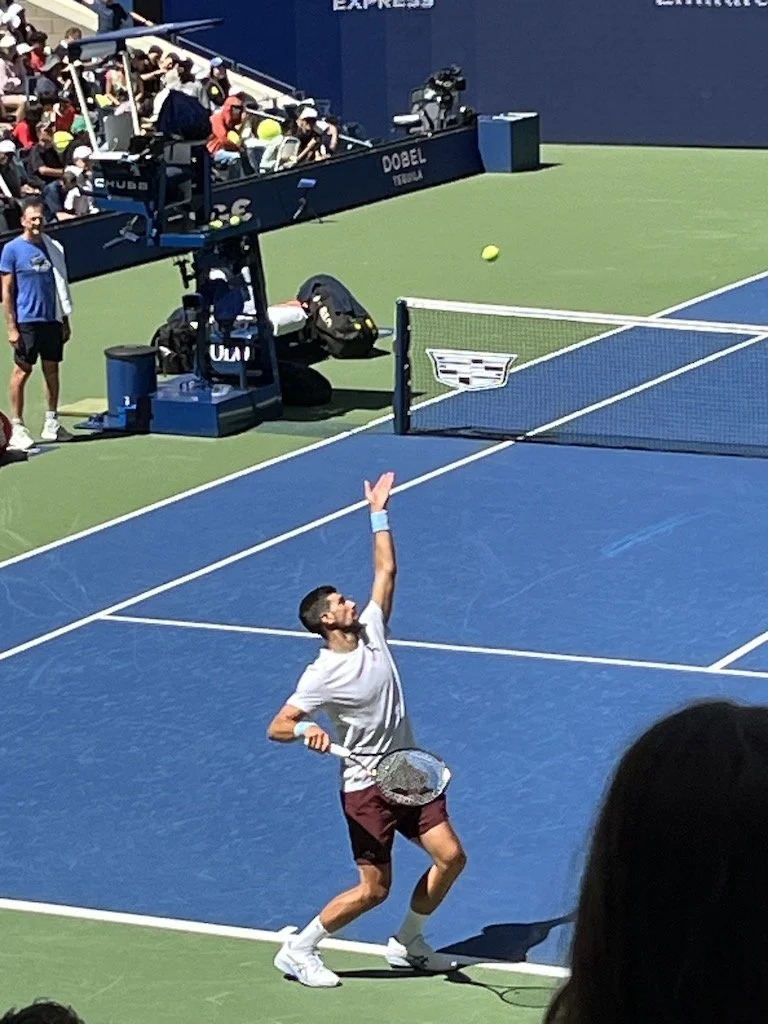

So Friday, Sept. 5, Novak Djokovic will play Carlos Alcaraz in the first semifinal of the US Open men’s singles championship — a match that virtually everyone sees as a fruitless quest to win his 25th Slam singles title and thus break the record he holds with Margaret Court.

Even if by some miracle Djokovic could beat the magnetic, mercurial Alcaraz, he undoubtedly would have to play the flawless, flawlessly robotic Jannik Sinner on Sunday, Sept. 7. It’s the kind of back-to-back challenge that Djokovic faced and met many times in the last decade. Now 38, however, it seems an unattainable double bill, even though this will be his fourth Slam semifinal appearance this year — a not-too-shabby achievement in a career of not-too-shabby achievements — one that has brought him full circle.

He himself alluded to this in a press conference earlier in the tournament in which he said there could be a third guy to turn the Sinner-Alcaraz rivalry into a trivalry. He was rooting for a third guy. “I was the third guy.”

As the 2010s dawned, the public had settled into what it saw as the Roger Federer-Rafael Nadal years. But their rivalry always existed more in the marketing sphere than it did in reality. Five years older than Nadal, the elegant Federer had cemented himself in the public imagination, aided by the media and the literati, as the archetypal tennis player, as he spent his earlier career playing people past their prime (Pete Sampras, Andre Agassi) or those who never materialized (Andy Roddick).Some had the passion but not the outsize talent (Lleyton Hewitt). Some had the talent but not the outsize passion (Marcelo Rios, Marat Safin). All were opponents rather than rivals.

Then along came the macho Nadal, in his sleeveless Ts, clamdiggers and bandanas, the pirate king to Federer’s preppy. But once Nadal arrived, it was over for Federer. In 40 matches, Nadal beat Federer 24 times. If the public somehow loved what was actually a fairly one-sided rivalry, Federer didn’t, breaking down on the court once and saying he couldn’t take it. He also said he never wanted a rival.

But that’s not what the public saw in the friendship that played out in marketing campaigns. And it’s not what the public saw in its collective consciousness. Into that consciousness wandered the crisp, endlessly color-coordinated but quirky and edgy Djokovic, the perpetually third-ranked player who was good enough for a semifinal match against one or the other but rarely good enough for the final victory. That is until 2010 when a change in diet, a new mindset and a Davis Cup win for his native Serbia set up the first of three years in which he would win three Slams a year (2011, 2015 and 2023).

All those years Federer was playing Nadal, Djokovic had been waiting in the wings — and watching. Playing them, often back to back, getting his brains beaten out by them, had taught him something. A journalist once told him it was a shame that he came of age in their era, because he would’ve won more without them. But Djokovic volleyed back that he would’ve won less. “They,” he said, “were the making of me.”

The public didn’t care. It had its rivalry. It didn’t want an interloper, not one who was at once perfectionistic and too eager to please, hot-tempered, rough around the edges and from a country that had been bombed by NATO for its role in the Balkan Wars. Djokovic’s later bungled response to the Covid crisis and his own personal anti-Covid vaccine stance, which led to a disastrous standoff with an equally responsible Australian government, would calcify his image as the punk fans loved to hate. It didn’t matter that by then he had become a gracious, cultured polyglot and philanthropist. Or that from a sheer tennis standpoint he was racking up the wins and the records, developing a rivalry with Nadal (31-29), who wasn’t too crazy about being eclipsed so soon at No. 1 and dropped his friendship with him; and even Federer (27-23) that was far more of a taut seesaw than the Federer-Nadal rivalry ever was.

Djokovic is the only one who holds a winning record against the other two. If you put all the weeks he was at No. 1 together (a record 428, plus one more he’s owed when Sinner was suspended), they would total more than eight years.

None of it matters. This weekend he’s back to being the third guy as the Federinas and Nadalistias imagine Sinner-Alcaraz to be Federer-Nadal 2.0. But Sinner, less balletic than Federer, is more of a freckled, Titian-tressed Ivan Lendl, while Alcaraz is less consistent than Nadal in his prime. Both Sinner and Alcaraz seem more gracious to their opponents than Federer and Nadal were. In that the New Two share something with Djokovic, who’s great at mentoring young players, even as he is still straining for a kind of public love that he will never attain.

Yet he’s the third guy who broke through, which begs the question: Who will be the next third guy, the one who “rises up to the challenge of a rival” (“Eye of the Tiger”) when Djokovic finally exits, taking the ghosts of Federer and Nadal with him? Tennis writer Charlie Eccleshare had a terrific piece in The New York Times about tennis’ “sandwich generation” — the men born in the 1990s who were overshadowed by the Big Three and then eclipsed by the New Two. The comments were pure tough love, with posters saying the Alexander Zverevs and Dominic Thiems simply weren’t good enough or squandered their chances.

But there is another way to look at it: They played the hand they were dealt. I once had a similar conversation with no less than Patrick McEnroe, who’s had a great career as a tennis player, coach and commentator but who was never the player his brother John was. His mother worried about that when he was young and starting out in tennis, but he told her he was fine with it. And I told him about a quote by Henry Jackson van Dyke Jr., a diplomat-educator-author-clergyman who wrote, "Use what talents you possess. The woods would be very silent if no birds sang there except those that sang best.”

You look back and think had Djokovic not misstepped in the pandemic, might he have already won his 25th Slam title and been done with tennis? Maybe, maybe not. I often think that life affords us all only so many wins and losses.

Djokovic, the eternal third guy on the court of love, has used his talents and drive to become the defining male tennis player of his — or maybe any — generation. It remains to be seen if Sinner or Alcaraz will one day be able to say that of himself.